Memorial Day in Southeast Texas

Rooted Therapy and Wellness in Beaumont Helps Those with PTSD or Childhood Trauma

For generations, Southeast Texas has been sending our sons and daughters to fight in World War I, World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Panama, and the Middle East.

For generations, Southeast Texas has been sending our sons and daughters to fight in World War I, World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Panama, and the Middle East.

Not all make it home. Those who do are broken. Many are broken in ways we can’t see.

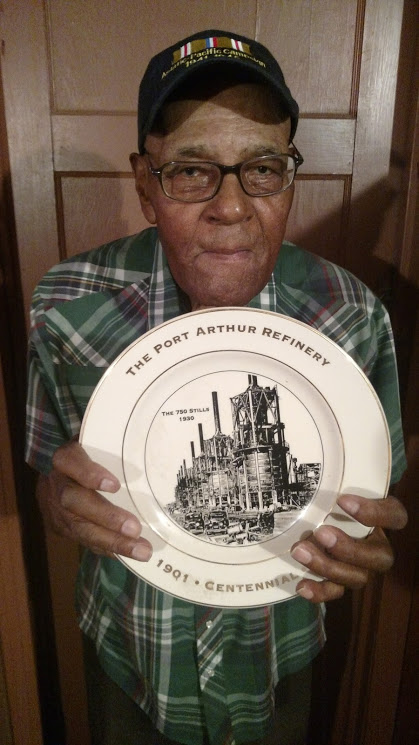

I met a man in Port Acres, Harrison Hill, who remembered his uncles going off to World War I. Before they left Louisiana they were happy, spirited young men. When they came back, he described them as “ghosts of their former selves”. There were no pyschological services for his uncles, or any World War I veterans when they came home, no treatment for PTSD or wartime trauma.

Harrison was a teenager when World War II came around. He was drafted. As a Black man, his options for service speciality were limited. He became a truck driver moving from island to island across the Pacific Theater. Supplies would be offloaded from ships, loaded onto his trucks, and then be put on airplanes making their push closer and closer to Japan. He saw bodies and body parts stacked like cord wood, Japanese and American alike.

Many soldiers went through that experience. Some were traumatized. Others managed to cope.

Hill’s real PTSD came on the day he was told that they had loaded the first atomic bomb on a plane bound for Hiroshima. He was just a farm boy from Louisiana, who didn’t have a lot of interest in the war before he was drafted. He became obsessed with the thought that the first atomic bomb had been on his truck, that he’d played a direct role in killing an unthinkable number of people, strangers, innocents.

No one in the chain of command would confirm or deny whether or not the bomb had been on his truck.

When he came home, like his uncles, there were no real resources in place to help Harrison Hill deal with trauma, with his PTSD. He did his best to cope. He went to work at the refineries in Port Arthur. The job was good. He built a home for his family, pounding in every nail himself. His pride was his garden. It reminded him of the farm back in Louisiana. It also kept his family fed with fresh, wholesome food. Tomatoes, corn, squash, okra, peppers. There were also fruit trees. The fig trees grew to great size over the decades after the war.

His life should have been ideal, but that untreated trauma nagged and nagged at him. At times, the guilt was overwhelming. Even on the best days, it didn’t leave completely. He did his best to bury the pain and trauma deep in his chest, but it constantly threatened to break free. Like many veterans from World War II, he kept his own council. He never told anyone about his guilt or pain. He never told the wife that he loved. He never told the children that he loved. There was no therapist or psychiatrist to tell.

When we had our talk, Harrison Hill unburdened himself for the first time. He cried while we talked. He said it was the first time he’d cried in decades. He also told me that that it was the first time since finding out about the atomic bomb that he’d felt any relief. Just saying the words out loud, sharing his pain, minimized it somehow.

It was a moving experience for the veteran, but it was a moving experience for me as well.

For forty years, I’d been dealing with my own trauma, my own PTSD. I’d never served in war. I’ve never seen the dead bodies of my comrades stacked up on the side of the road. I did face my own battles though, almost daily from the time I was five years old. My father outweighed me by two hundred pounds. He’d been an athlete and a prison guard and an oilfield roughneck. He was strong, and he hit me as hard as he could with sticks and belts and my toys. He hit me in the head with wrenches, screw drivers, small hammers, metal coffee cans, and the dull side of a machete. They were daily battles I had no chance of winning. I absorbed pain without being able to dish any out. I also saw my brother beaten, and I was powerless to protect him.

Like the veteran, I pressed my trauma down as deeply as I could. Like the veteran, the PTSD was always with me. I had physical pain from my father’s beatings, emotional pain from my mother’s refusal to help me, and guilt from not being successful in protecting my younger brother.

I used the veteran’s example to start looking for help. I’ve talked to psychologists and therapists and psychiatrists. I’ve ended contact with my parents. They didn’t hit me after I left home, but they found other ways to hurt me. All of that helped.

Working with Rooted Therapy and Wellness in Beaumont has given me a broader range of tools to heal. I have access to guided meditation, cupping, massage, aromatherapy, vagus nerve exercises, medicinal plants, and more.

I feel better. I’m getting stronger. Every week, I feel like I have a better chance of having a longer, healthier life.

Do you know someone struggling with trauma or PTSD? It’s not just soldiers. It’s women who have been in abusive relationships. It’s your neighbor who is quietly doing his best to recover from child abuse. It can be the kids next door who suffered through their parents’ brutal divorce.

If you can, encourage them to get help. The sooner they deal with their own trauma the easier (and very likely the longer) the remainder of their lives may be.

Rooted Therapy and Wellness Beaumont

Women’s Health Services for Southeast Texas Moms

7102 Phelan Boulevard in Beaumont

(409) 790-0014